XLR8R Artist Tips: KMRU

As KMRU, Joseph Kamaru, a 26-year-old sound artist from Nairobi, Kenya, sits at the forefront of modern experimental ambient music. Now based in Berlin, Germany, where in 2020 he enrolled in a graduate program for Sound Studies and Sonic Arts at the Universität der Künste, KMRU has released several albums, on labels including Warp Records, Seil Records, and Editions Mego, which is where he released Peel, his debut album of delicate, textural compositions, in 2020—shortly after he’d made a name for himself with his more beat-driven songs with a performance at at Nyege Nyege festival.

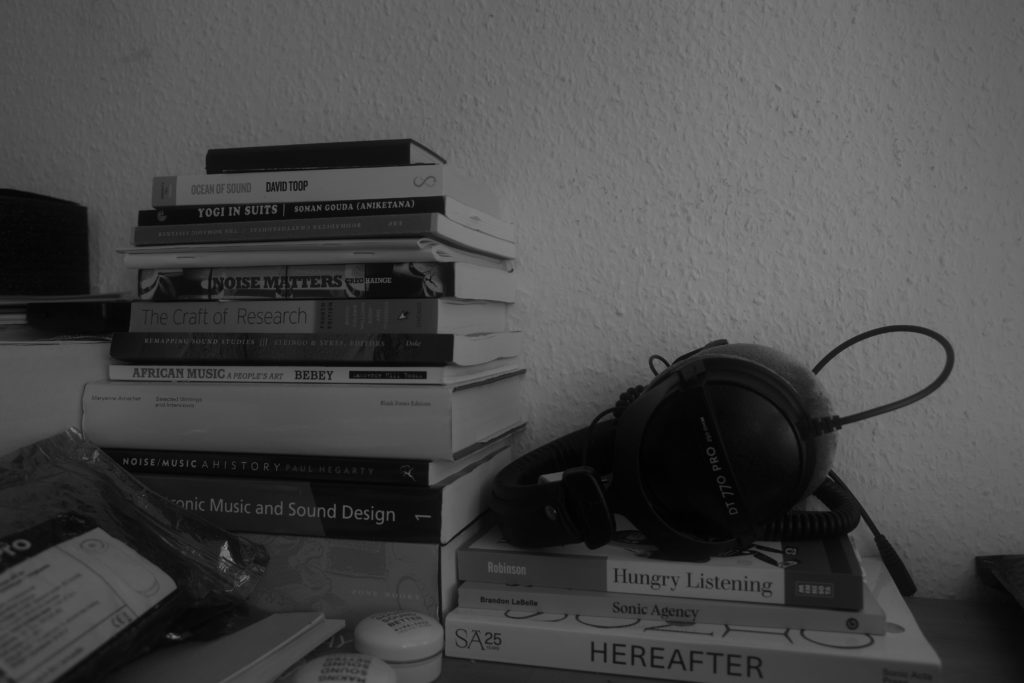

Across all of Kamaru’s recent tracks, including on Epoch, which he released in October, he delivers an exquisite mix of evocative and moody textures, some of which are between 10 and 20 minutes long because they unravel at a repetitive and leisurely pace. At the heart of them all you’ll find Kamaru’s field recordings, recorded out of the window of his Berlin apartment or when roaming the streets of Nairobi, where he grew up and began making music in university using computers that came equipped with the digital audio workstation FL Studio. With the help of a classmate, he eventually learned Ableton Live and signed one of his first songs to German label Black Lemon, but something inside Kamaru was drawn to textural sounds.

One day, during a train journey from Nairobi to Kilifi, he became entranced by the train’s sounds and began recording them into his IPod. These sounds eventually became his EAST EP, released with Manch!ld, whom he met on the train, in 2017, and led him to discover the work of experimental musicians like Slikback and Dj Raph. “Recording outside, with my headphones on, I realized there was so much sound around me,” KMRU told Pitchfork. “ Armed with these sounds, he’d return to his laptop, which is normally positioned at his kitchen table, and morph and stretch them into these hazy tracks. For this edition of Artist Tips, KMRU sat down with XLR8R and told us how he goes about it and some of the key practices at the center of his work.

01: Follow Your Intuition, Rather than Analyse

When I am writing ambient works or textural-based compositions, I try to follow my intuition. I write my best music when I feel completely attuned to the music, so much so that I actually forget what I am doing. At no point am I consciously thinking, Ok, I am going to this synth or this setting, then connect it through this pedal. I just take the synth and take the pedal and just mess around.

To do this, you must not set predetermined goals; instead, as you progress through a track, make choices that feel right in that moment. Start a project without a clear goal, using sounds and instruments that you select, and do not undo anything. Create a 20 or even a 60-minute loop and then make a really short track. Rather than analysing what you’re doing too much, just follow your intuitions. Your instincts. Your body, the space you’re creating, and the tools you’re using have to be intuitively synched.

It’s not easy to find this headspace but I do have some rituals. Like ways where I get myself into this state of creation. What I normally do is open the software and just play around with sounds. Then at some point I get this Oh, Aha moment and slowly I get lost in the music. I become calm. If I don’t find this space then I feel frazzled and I think too much and what I make doesn’t make sense. Yes, there’s too much thinking going on!

I also suggest that if you’re used to starting a piece of music with a metronome or a specific BPM, try not to. Instead, take an instrument, either hardware or a software plugin, and hit record on your DAW. Listen before you play any sounds of the instrument; this will enable you to become attuned to the space you’re working at. Listen before you record. Be patient.

Another thing I like to do is turn off the grid on my DAW, such as Live. If you press ctrl +4 on Ableton the grid sort of disappears, and this helps me to break away from the confines of the software, so you can create in new ways!

I also use software like Maxmsp to explore vertical ways of composition. And when recording sounds with plugins, I think it’s good to bounce the tracks in place (as audio) and move on, rather than going back to figure out the sounds and settings used. I also recommend using basic synthesis to create sounds: sine waves, saw waves, and field recordings too.

You can hear this effect on “Odra,” which I started with my Lyra 8. My Lyra 8 is an organismic synthesizer and the beauty about this synth is that it never sounds the same; if you want to record something you always have to be present with it, listening and recording. The process was simple: I’d capture sounds with the Chase Bliss Mood pedal and layer in improvisations from the Lyra. I wouldn’t ever go back to the recorded sounds after; rather I would build upon what was already created.

Often, when you do this, you’ll end up with long-form compositions done in one take, but they’ll sound fantastic. Authentic. This is the same process I use on most of my tracks. If the track is long, you can let it be, but you can also cut them down if you want to.

02. Use Subtle Repetition to Engage the Listener

I like to explore different repetition patterns of a specific sound in my tracks, so laying the same sound across different positions. For example, sometimes I’ll capture a pattern on a pedal and record the sound into the project, then I’ll slowly move the volume knob and fade it in and out, adding subtle gestures from other parameters—delay, etc.— as well.

I also like to record longer loops which have different permutations and I’ll add inversions of those loops within the main loops. The whole Peel album feels like this. It’s really just long and short loops interacting with each other.

Sometimes the sounds might be off but that’s ok, unless it feels really wrong! I think it feels as if something is happening but it’s not really happening. I would suggest is that you use the effects quite subtly and slowly. Lightly. For some tracks I’ll be sitting there for hours, twiddling with the volume knob, recording in automation on the track, so the effect is tiny, tiny. This is especially true for long durational tracks, or those with lots and lots of layering. On “Peel,” the track, you can hear that the volume drops out in the 12th minute because my hand was tired, though nobody has ever mentioned it! My experience is that this effect really engages the listener.

03: Drive, or Score, with a Field Recording

One of my favorite recording techniques is to begin a track with a field recording, which forms the basis for the composition. What I’ll do is make a recording, maybe on my phone through my window, perhaps of a bird flying past or something. I will then use those sounds to guide the piece that I am creating.

Normally the recording will be the skeleton for the track. Like it’ll be the focus or the lead. It carries the piece. On other occasions I’ll just use that recording as an idea and I’ll score a film for that moment. That motion. Or whatever it is. (That was the case with “Tor,” which is based on a field recording a friend sent to me in 2018.) Taking an instance or phenomenon from the outside and contextualising it through sound can be an interesting approach to explore.

My daily walks are central to this process. When I’m in Berlin, I love going for walks along the Spree and recording there. (You can hear some of these recordings in “for sure I saw him” from my as it still is EP.) I will walk for around 10 minutes, and I’ll never cut or edit the recording in any way.

Once I’m back in the studio, I’ll drop the recording into my DAW and then the work begins. Normally I will choose one instrument to use for the composition of the entire piece. I’ve found that limiting myself to one instrument provokes more possibilities of what you can do with the one sound. I’ll edit, layer, and process the sounds of the instrument, but the field recording is what drives the piece.

I’ve used this technique a lot in my music. “life at ouri,” for instance, was based around a jam I made on a friend’s piano in Montreal, when the window was open when I was playing. Also, “Walking Dreams“: it’s an old track but I remember it because the recording was done when I was walking home from a night out in Nairobi. I used a field recording from my phone, then I added all the layered sounds around it. The field recording isn’t edited in any way.

I would also like to talk some more about limiting yourself in terms of equipment. Spending time honing an instrument or piece of gear will inspire a more tactile connection with equipment. I’ve come to love producing on my kitchen table because it’s quite small so it means that I can’t have more than one piece of equipment, other than my laptop. It also faces out of the window so I find myself in a contemplative mood when I work from there. My favorite instrument to do this with is the Lyra 8. I use it both for live performances and production, mostly because of its uncertainties. It’s chaotic but beautiful.

04. Juxtapose the Loud with the Quiet for Maximum Impact

I’m really not sure whether this is a thing but I use it in my music a lot. With tracks that have lots of layers and tracks, I think that there are many sounds that aren’t actually heard but they can be somewhat perceived by the subconscious ear. Therefore, they impact the listeners’ experience with the music.

So, while adding sounds to a project, I like to experiment with relatively low volume sounds and contrasting sounds that will respond to the low sounds. I’ll intentionally record sounds at low volumes to contrast with the higher volume sounds. So you’re sort of juxtaposing low sounding recordings with really loud or massive sounds. In my experience, this allows you to hear the sounds beyond the thresholds of the human ear. In Tennyson’s track “Like What” they do this really well. They play with sounds and it feels like you’re in a building and you’ve moving in different spaces in the house.

I find the technique works best on long-form tracks or drones which evolve over a long period. With “while we wait,” for example, you can hear the literal clicking sounds from my Lyra 8, and though they’re quite subtle they carry the piece. The whole concept of the track came from the click sounds during a jam on the synth. And I thought it would be interesting to dive into this immersive world of undertones of the Lyra and low field recorded sounds.

I also recommend that you try listening to the tracks in different listening environments: listening in a room with windows open, on your phone, or even outside. Note down every difference you hear in these environments. There’s no doubt that you hear new sounds from the piece based on the listening conditions. That’s because the piece feels different in different spaces and rooms. Sometimes I even like to play out a track out loud through the speakers and record the sound with microphones and use the new sounds layered with the original track. That’s just another way of listening. This really helped when I was recording Peel, where different overtones would emerge depending on the spaces where I played it.

05. Omit The Main Element for More Perspective

In ambient or experimental music, the main element of the piece can be any sound, which is different to, say, pop music where the vocals have to be mixed perfectly with all the other instruments. Because of this, there’s so much more flexibility.

One thing I like to do, then, when a piece of music is finished, is mute one significant element before rendering. This gives a different perspective to the track when listening back, which is important when you’ve been working on it for an extended period. Sometimes the track doesn’t need that element, and this is a great way of identifying what you do and do not need. With “rimpa dusk,” for instance, and “Well,” these were recorded in only one take and I ended up muting various sounds. I did this because I thought they needed less clutter, and they sounded better without the main instruments and sounds!

Another thing you can do is reverse the whole track once it’s finished. On Jar, the first track is called “Degree of Change” and the last track is called “Change of Degree.” What nobody knows, until now, is that these are actually the same track, only reversed! Some tracks will sound wildly amazing when reversed, but others don’t.

Finally, you can change the pitch. Plugins like SoundShifter (waves) are ideal for this. I’ll often pitch the entire track a few pitches higher, work on it in the new pitch, and return to the original key. On other occasions, I’ll just listen to the music in different pitches to see how they sound. This is sure to give you some fresh perspective!

All photos: Artist’s Own

Source: XLR8R